This essay would normally be part of my paid subscription, but as a special Easter treat, I wanted to give you all a glimpse of what goes on behind the paywall.

In February, I published a poem inspired by the “alabaster jar” stories in Luke 7:36-50, Matthew 26:6-13, Mark 14:1-9, and John 12:1-8.

Only John named Mary of Bethany as the woman who anointed Jesus, whereas Matthew, Mark, and Luke kept their female protagonists anonymous.

Given the similarities between John 12, Matthew 26, and Mark 14, I am inclined to believe that all three describe the same event.1

The most significant difference between the three is the fact that John describes Mary pouring her perfume on Jesus’ feet (Jn. 12:3), whereas Matthew and Mark describe the woman pouring it on his head (Matt. 26:7; Mk. 14:3).

This detail is far from trivial since the anointing of Jesus’ head carries tremendous theological implications,2 which we’ll explore in just a moment.

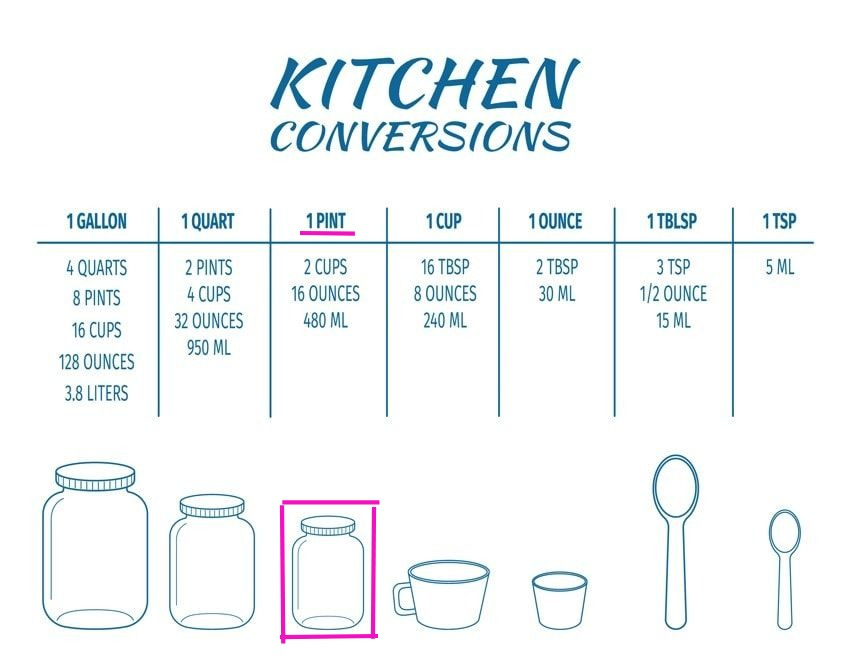

However, as far as my theory goes, I would like to point out that John describes Mary pouring “a pint of pure nard” (Jn. 12:3 NIV) on Jesus’ feet.

Matthew and Mark don’t detail a precise volume, but all three accounts describe the perfume as being worth “a year’s wages” (Jn. 12:4; cf. Mk. 9:4 NIV) or “a high price” (Matt. 26:9 NIV).

Ladies and gentlemen, we’re not talking 50 ml of Ariana Grande’s Cloud Pink.

We’re talking two cups of rich, aromatic oil.

Purely for the sake of argument, I would like to suggest that two cups of perfume would have been ample supply for anointing Jesus’ head and his feet.

However, since there’s a unique purpose for all four Gospel narratives, it is worth studying each story within its respective literary context to appreciate the specific theological truths each writer wanted to emphasize.

In the spirit of Easter, let’s begin our study of Mary’s alabaster offering in Mark 14.

Mark 14:1-9: A Messianic Anointing

MARK 14:1-9 (NRSV) It was two days before the Passover and the festival of Unleavened Bread. The chief priests and the scribes were looking for a way to arrest Jesus by stealth and kill him; for they said, “Not during the festival, or there may be a riot among the people.” While Jesus was at Bethany in the house of Simon the leper, as he sat at the table, a woman came with an alabaster jar of very costly ointment of nard, and she broke open the jar and poured the ointment on his head. But some were there who said to one another in anger, “Why was the ointment wasted in this way? For this ointment could have been sold for more than three hundred denarii, and the money given to the poor.” And they scolded her. But Jesus said, “Let her alone; why do you trouble her? She has performed a good service for me. For you always have the poor with you, and you can show kindness to them whenever you wish; but you will not always have me. She has done what she could; she has anointed my body beforehand for its burial. Truly I tell you, wherever the good news is proclaimed in the whole world, what she has done will be told in remembrance of her."

Why the angry reaction to this alabaster offering?

When the woman in this passage (whether Mary or another) anointed Jesus’ head, her actions were met with ἀγανακτέω, a Greek word denoting intense anger, rage, or indignation.3

Within the Gospels, this specific kind of anger or indignation is exclusively aimed at someone who either claims, requests, or receives power and authority due to God alone.4

If this woman’s transgression was wastefulness (as her critics claimed in v. 4), why did Mark use such strong language to describe the reaction she received?

The cultural tradition behind anointing

Within Israelite tradition, an anointing of the head was reserved exclusively for prophets, priests, and most importantly, kings—persons who had been appointed by God to fulfill a specific task for the nation of Israel.5

The significance of such a ritual, so intrinsic to the cultural and collective memory of the Jews, would have been obvious to those who witnessed it.6

And to Jesus, for that matter—although he knew far better than anyone else what his anointing foreshadowed.

The two-fold purpose of Jesus’ anointing

Jesus declared, “She has anointed my body beforehand for its burial” (v.8), a point of significance because Jesus’ body never received an anointing after his death.7

To fully appreciate the implications of this woman’s actions, consider the timeline of events that unfold next:

The scene in Mark 14:1-9 occurs two days before Passover and Feast of Unleavened Bread. For Israelites, these festivals were reminders of God’s deliverance both from oppression and death.8

The timing here is no coincidence. The correlations between Jesus’ anointing and the Passover foreshadow a promise of deliverance far greater than the exodus from Egypt.

As the curtain falls on this scene, Judas’ betrayal, the Last Supper, Jesus’ arrest, trial, crucifixion, and resurrection follow one another in rapid succession.

Yes, the woman in this story anointed Jesus for his burial, but her priestly service also signified something far more profound: his kingship over death.

Jesus needed no anointing after his burial because the grave no longer held any power over him (see Mark 16:1-6).

This is the great hope of Easter: We have a king who not only died in our place but who reigns victorious over death—and in Him, we, too, need have no fear of the grave.

Glory Hallelujah!

Thank you for reading! If this essay resonated with you, I hope you’ll prayerfully consider becoming a patron of Daughter of the King:

Based on my cross-textual analysis of Matthew 26, Mark 14, and John 12, I believe there is enough narrative consistency between the three accounts to support this theory. The details of Luke’s account, by contrast, differ so strongly from the others in timing, setting, and dialogue that I believe Luke was describing an entirely different event.

However, some biblical scholars would disagree with my theory. I encourage you to study other commentaries to gain more insights and formulate a well-educated understanding of the text(s).

Santiago Guijarro and Ana Rodríguez, “The ‘Messianic’ Anointing of Jesus (Mark 14:3-9),” Biblical Theological Bulletin 41, no. 3 (2011): 133.

Ceslas Spicq and James D. Ernest, “ἀγανακτέω,” in Theological Lexicon of the New Testament. (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1994), np.

cf. Matt. 20:24; 21:15, Mark 10:41 & Luke 13:14.

Carol A. Newsom, Sharon H. Ringe, and Jacqueline E. Lapsley, eds., “Gospel of Mark,” in The Women's Bible Commentary. Revised edition. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2012), np.

Santiago Guijarro and Ana Rodríguez, “The ‘Messianic’ Anointing of Jesus (Mark 14:3-9),” Biblical Theological Bulletin 41, no. 3 (2011), 136.

See Mark 16:1-6

John T. Swann, “Feasts and Festivals of Israel,” in Lexham Bible Dictionary. n.p.

So many Marys!

I was just starting to write a comment and noticed the woman before me already wrote it. I could say so much more because you have moved me to tears but I am guilty of rambling. I was ready to begin my devotions and picked up my phone as I gathered my books paper and pen and saw a picture of your Part II on the screen. I ignore most notifications but this one said, (Please read this) Daughter of a King (you are). So I went back to Part I. I don’t even know how I connected with you but I consider it nothing less than a Divine intervention. I’m so grateful. Thank you. Now on to Part II.

Deb